Colleen Mullins

San Francisco, California

colleenmullins.net/section/382046-Book-Works.html

Expositions are the timekeepers of progress

2020–2021

Archival pigment prints on 100gsm Hahnemuhle Rice paper, with Post-it paper and Tops ruled paper inserts; Wrapper hand-cut Bristol board with tipped in colophon and artist statement

8.5” X 6.25” X .75”

Artist Statement

Expositions are the timekeepers of progress is an examination of monument removal, seen through the eyes of one Northern California town and its statue of William McKinley, removed in 2019. The book draws its narrative from conflicting stories and histories of the president, the statue, and the process of a community both coming together and falling apart over an effigy that arguably never belonged there.

In early 2019 it became the first Presidential statue removed from public view in US history.

Nationally, the debate surrounding monument removal oftentimes settles into clearly delineated talking points. The momentum of the removal movement in the past few years was a key factor in Arcata’s decision to remove their statue. Yet, the narrative that emerged around McKinley as justification for removing his edifice was rife with historical inaccuracies, half-truths, and distortions—including the erroneous claim he was a slave-owner, when in fact, he fought for the Union in the Civil War. Further, to many in the town the monument was not a historical symbol but a local landmark; many locals remain completely confused even now as to why the statue was removed.

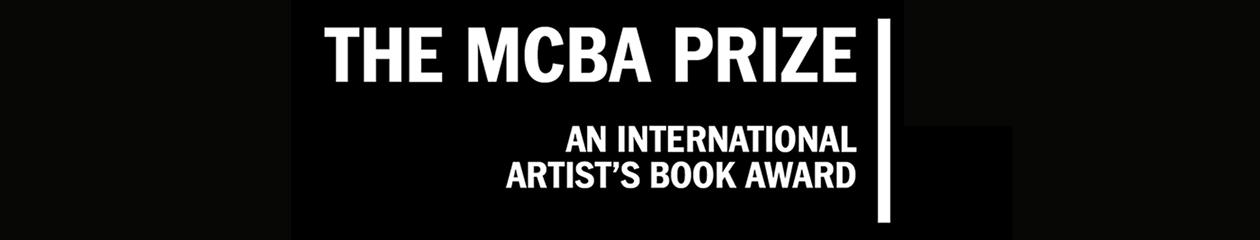

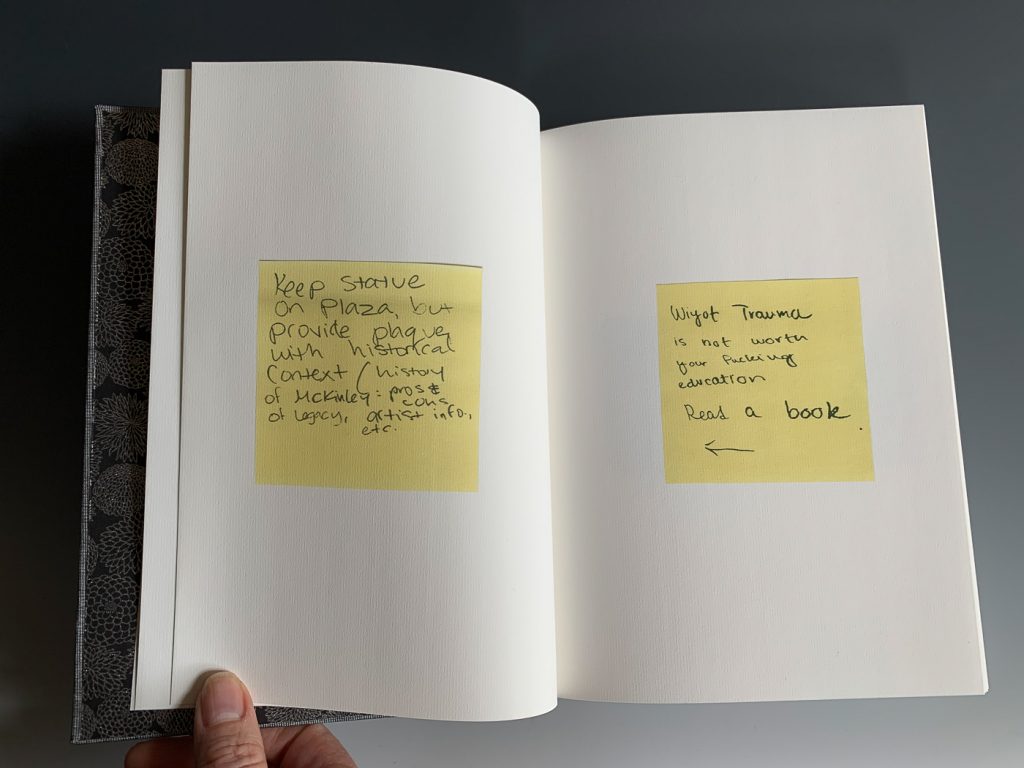

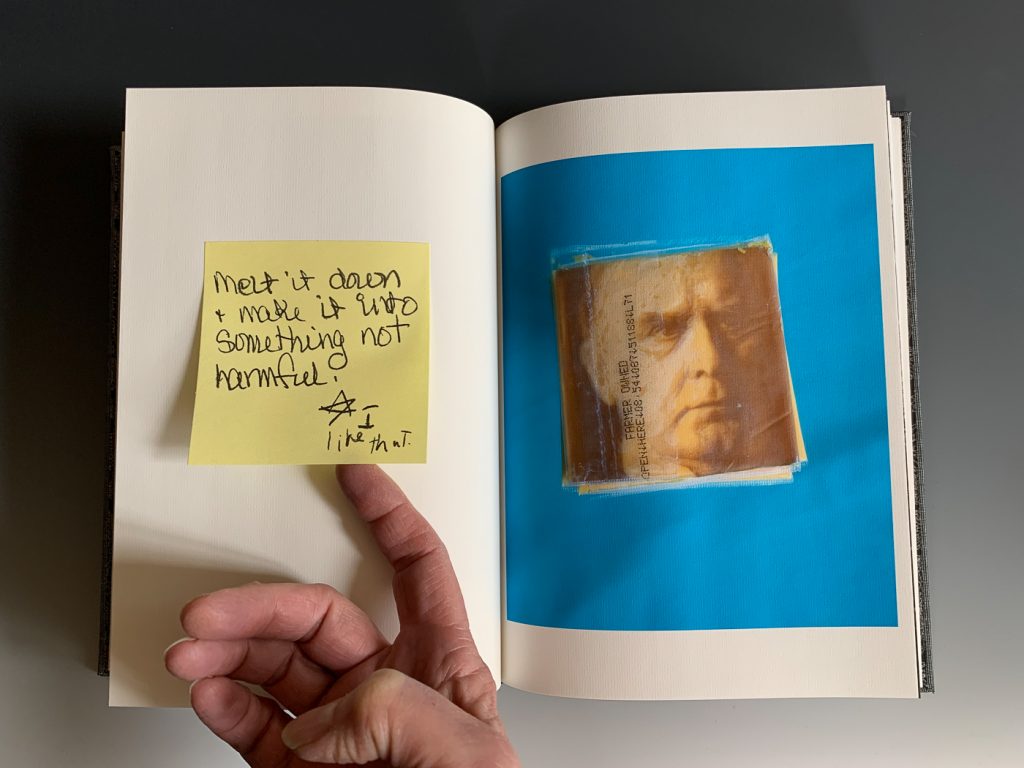

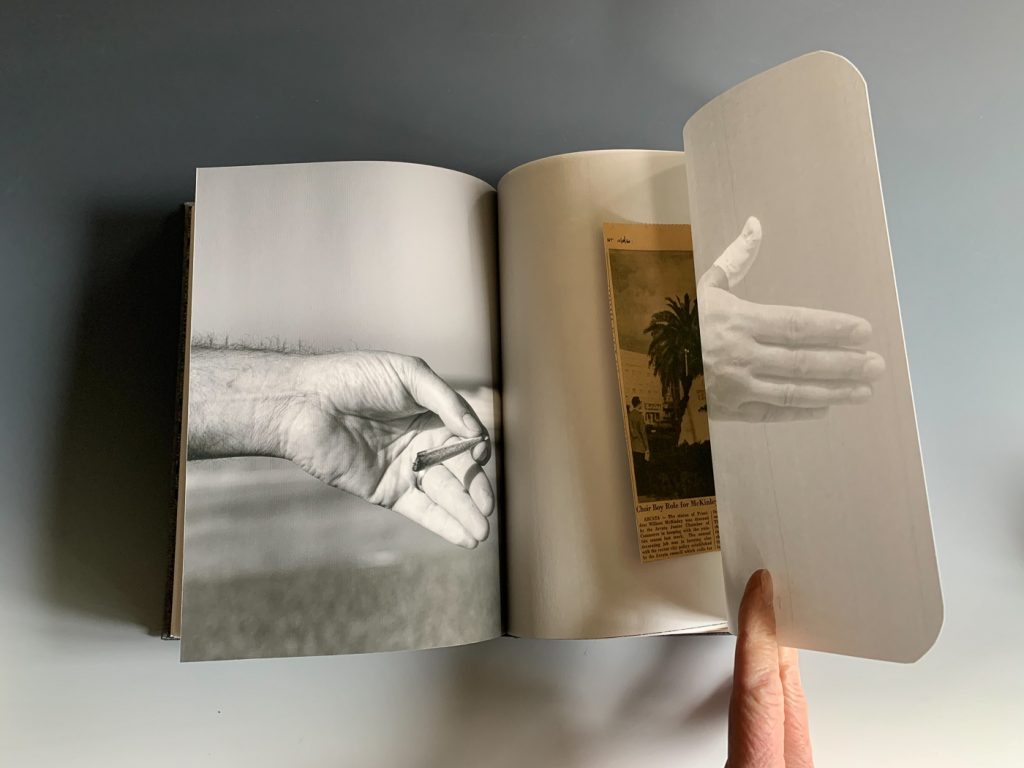

To tell this ambiguous yet fascinating story, Expositions uses photographic symbolism to represent the missing and mutable histories concealed within the espoused story. Original photographs are complimented by extensive archival material, news clippings, and even recreated post-it notes used to share opinions at a meeting debating the statue’s fate after yelling became a problem.

Over the 100+ years it was in place, the statue was climbed by jubilant students from the local university, defaced with caustic substances, had cheese stuffed in its nose, had its thumb sawn off (later recovered and re-attached), and decorated for holidays as everything from a choir boy in white-face to an angel. The statue was a talisman; a mountain; a meeting place. It functioned less as a symbol of white oppression of the native Wiyot, nor the imperialist tendencies of the president himself, but simply as a mascot. Yet, the robust conversations in the community, taken slowly and methodically, helped all sides to see each other, and led to a previously improbable act of neighboring Eureka returning Wiyot land, stolen in 1860 after a brutal massacre.

In total, Expositions presents a balanced consideration of both the good intentions and uneven results of seeking restorative justice through monument removal.

Archival materials are recreated, hand cut, and tipped in, or inserted, as though the last viewer left a bit of evidence behind. The case is swaddled in a hand-cut Bristol board wrap, an empty plinth drawn from my own photograph of this statue. The work is an edition of 7 + 2 a/p