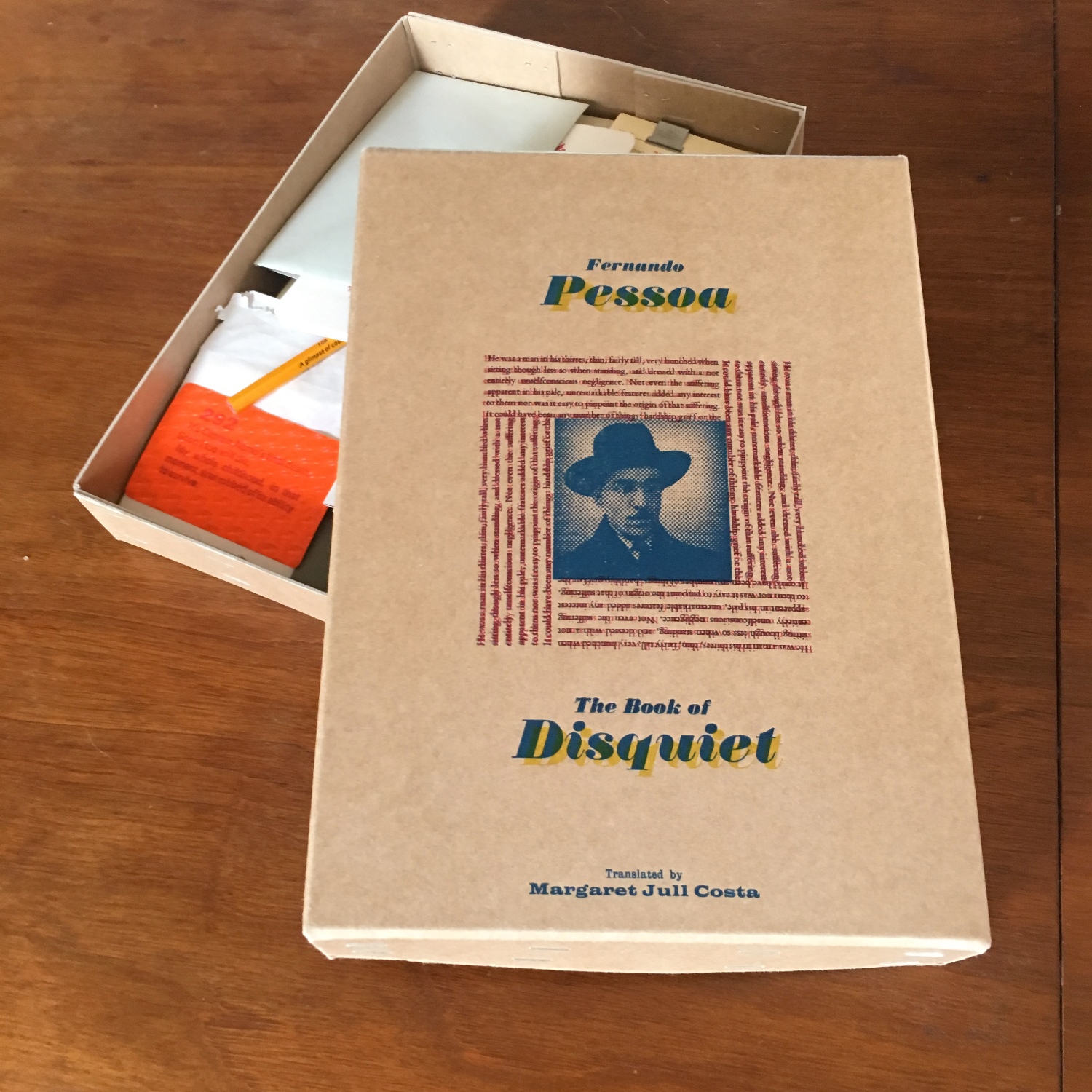

The Book of Disquiet opened.

The Book of Disquiet with contents.

The Book of Disquiet: box top with a selection of fragments.

A jumble of fragments from The Book of Disquiet.

Tim Hopkins

London, United Kingdom

https://thebookofdisquiet.

The Book of Disquiet by Fernando Pessoa

2017

Letterpress

80

n/a

Variable dimensions

280mm x 202mm x 42mm

https://vimeo.com/215534505

The Book of Disquiet by Fernando Pessoa; the Half Pint Press Edition

This edition of Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet takes a recognised classic and builds out from that book’s unique history, form and content to create a viable reading experience that adds to the feeling and atmosphere of the novel itself.

The texts that make up The Book of Disquiet were found in a box in Pessoa’s room after his death, in bundles of manuscript and typescript fragments and in no fixed order. It consists of the everyday thoughts of a single character, Bernardo Soares.

The Half Pint Press edition of The Book of Disquiet takes 61 of the hundreds of fragments, and presents them on a variety of paper and non-paper ephemera (some found, some made). Each fragment was typeset by hand and printed by hand on an Adana Eight-Five tabletop letterpress in an edition of 80. The fragments are presented unbound and with no fixed order in a hand-printed box.

This edition responds to the original’s form, or lack of form, by restoring disorder to The Book of Disquiet: the fragments are to be picked out as the reader pleases. This reflects the origin of the text itself and also makes possible connections between fragments which may be less available in a bound, ordered edition; Soares was prone to letting his mind wander during long nights in his room and the book gives a sense of that wandering mind. This form also nods to a history of unbound books, in particular BS Johnson’s The Unfortunates and Marc Saporta’s Composition No 1.

It writes Soares’s ideas across the everyday detritus of a life lived, on objects as diverse as a postage stamp, a compliments slip, a booze label, a page of accounts and an internal transit envelope. Not all the objects are paper: the box includes a pencil (a single-paragraph fragment, one line letterpressed on each side of a hexagonal pencil), a lollipop stick and a matchbook. Some are beautiful, others grubbily everyday. Likewise the box, which is deliberately not a cloth-bound fine press production but instead hand-printed on a commercially-available stitched board box. Each fragment has its own dimensions and character, and each was approached as a separate project, choosing type size, layout and fragment length in response (though care was taken not to relate the content of text too closely to its format, to avoid being boringly literal and closing down meanings).

The impression is of a box of belongings, each with a value of some kind to the owner. Each may be kept because it’s beautiful, or important, or useful, or attached to a memory: the reader can’t know but the form invites the reader to imagine those reasons, and therefore to engage their imagination more fully in the work. There is a melancholy sense of sifting through the relics of a life lived, full of unreachable connections. The edition enriches and enhances the experience of reading Soares’s words, anchoring them in the quotidian, explicitly an abstracted literature of everyday existence. Occasionally the fragments are difficult to read, but the most important part of the book remains Pessoa’s words, made yet more atmospheric by making the experience of reading more physical and tactile.

It is a book and not a book, everyday and extraordinary, hand-made and machine-made, real and impossible.