Veronika Schäpers

Karlsruhe, Germany

veronikaschaepers.net

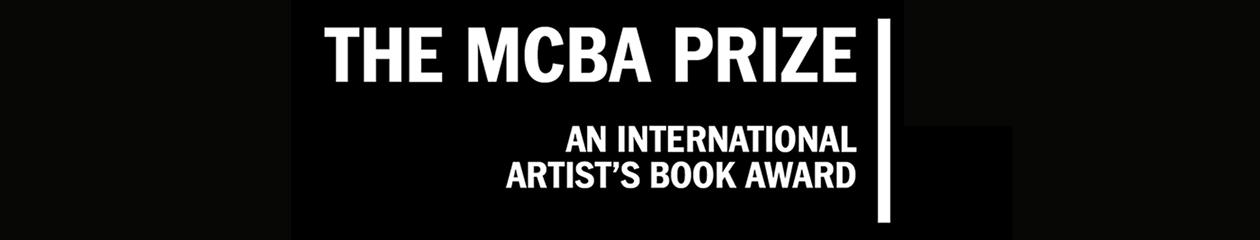

Das müssen Sie mir erst einmal beweisen / First you have to prove it to me

2021

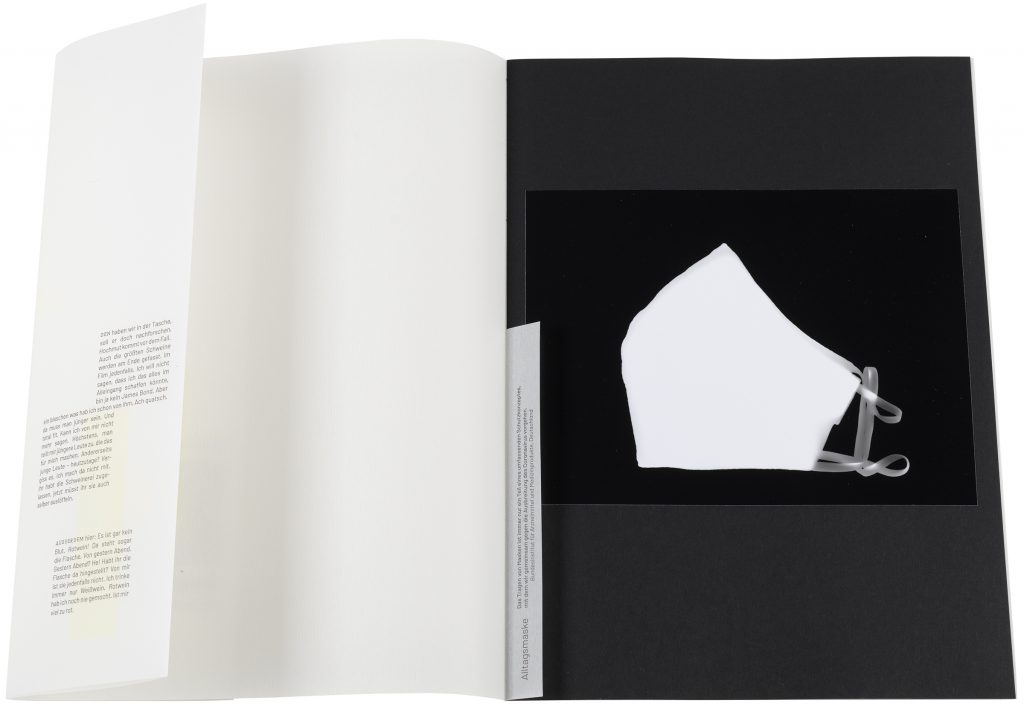

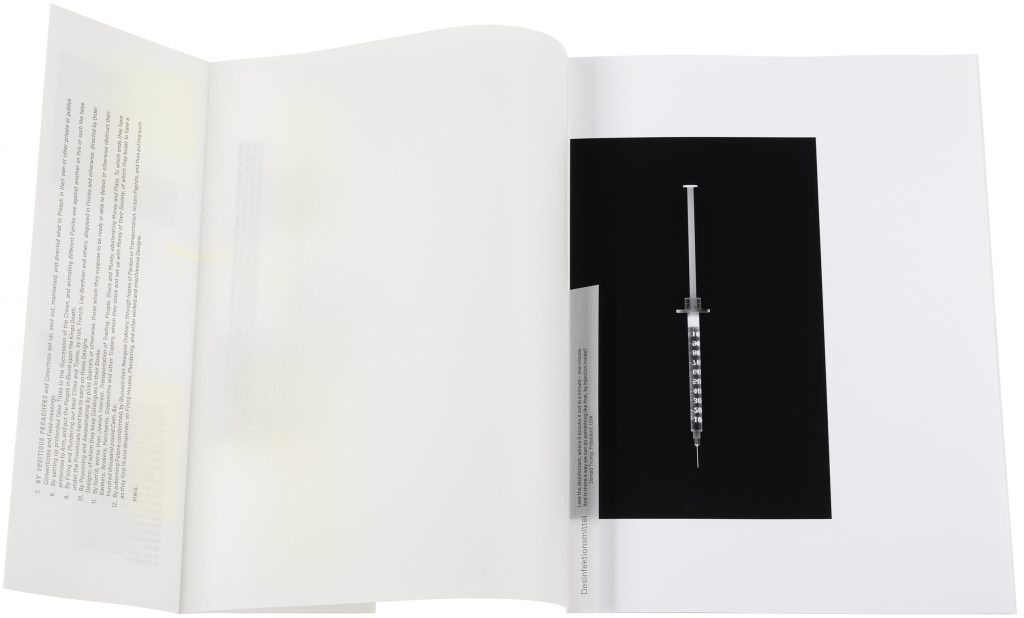

Letterpress from polymer plates on Enduro Ice-paper. 24 original b/w und color photograms on Ilford Multigrade Deluxe, Fomaspeed and Fuji Crystal Archive, laminated on Colorplan Ebony and Colorplan Bright White. Hinged slipcase in two colors, pasted with Efalin-paper and embossed title.

9,45’ x 13,38’

Artist Statement

Das müssen Sie mir erst einmal beweisen

First you have to prove it to me

In the spring of 2020, as the coronavirus spread first in China, then in Italy and finally across the entire globe, touching off a worldwide pandemic, more and more conspiracy theories also sprang up about the origin and spread of the virus. Social media and news networks played a major role in this; the established audiovisual and print media were vilified as »fake news,« and replaced by »alternative« sources.

At the start of the pandemic, for a period of two or three months when people still knew very little about the virus, a wide range of sometimes highly unusual methods were suggested as COVID-19 protection and treatment—often based on dubious scientific evidence or removed from their scientific context, making them incomprehensible. This was not a regional phenomenon; rather, it spread throughout the entire world along with the virus.

In March of 2020 I began to systematically collect different prevention measures and purported cures for COVID-19, and I discovered a connection between the dissemination of conspiracy theories and the quantity of recommended protective measures. The number of conspiracy theorists and proponents of alternative protective measures is remarkably large in the US and Germany, while during the same period in 2020 conspiracy theories played only a very small role among the populace in Japan and China.

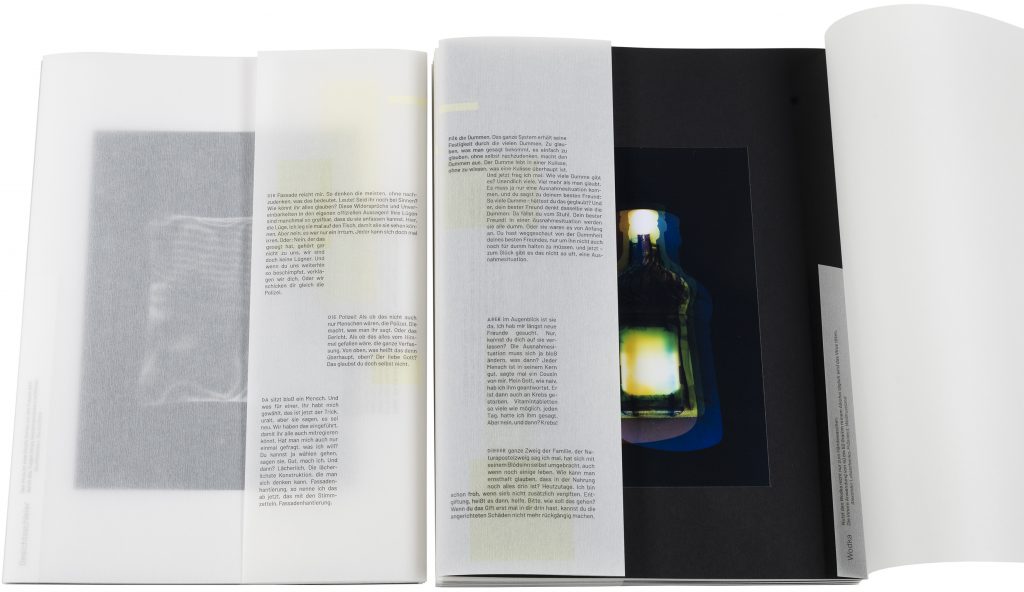

I chose 24 objects from my collection, which I captured as black-and-white or color photograms. The object is placed directly on or very close to a sheet of light-sensitive photo paper. It is then exposed using one or more light sources, developed, and fixed. On the one hand, the photogram is considered a true image or vera icon, since it claims to show a direct, unaltered image of the object. On the other hand, photograms may be described as images of the ‘neither-nor’ that flatly deny that they depict their subject matter, for what they show is never more than either half-present or half-absent, albeit always to the scale of 1:1. They are half truth, half fiction.

In particular, the aspect of a physically grounded alienation caused by the refraction of light—depending on the materiality of the object being depicted—along with the color inversion inspired me to use the photogram method, since it lends the objects a somewhat surreal aura. Five simple lemon slices, for instance, take on an almost magical coloring. In a way, they illustrate the arguments of conspiracy theorists who turn factual evidence into its opposite.

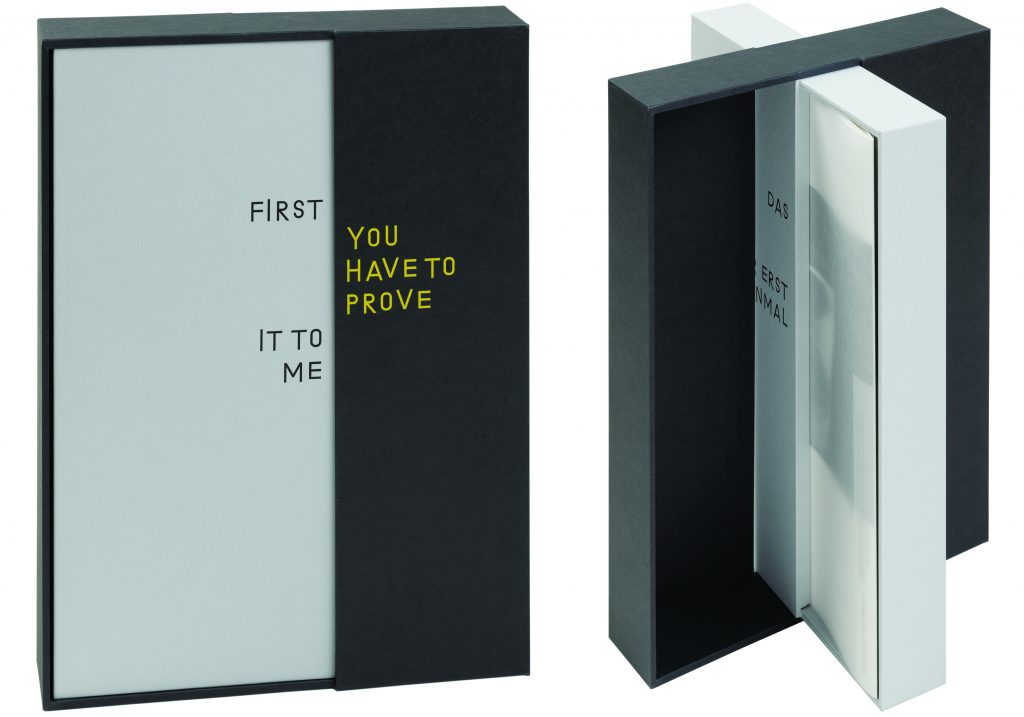

The 24 original photograms are displayed opposite two texts. One is an original short story by H.M. Hartmann written specifically for this edition, about a present-day conspiracy theorist, and the other excerpts Titus Oates’ publication on the Popish Plot of 1679.

Titus Oates, an English priest, was the main informant in the »Popish Plot,« which he invented in 1678. He claimed that English Catholics were planning to murder King Charles II in order to replace him with his Catholic brother, Jacob, and to carry out a counter-Reformation. Oates’ accusations set off a serious national crisis; at least 15 innocent people were executed before skepticism about his theory gained the upper hand and he himself was finally arrested, in 1681. In April 1679, in order to shore up his theory and emphasize his credibility, Oates published the text: »A true narrative of the horrid plot and conspiracy of the popish party against the life of His Sacred Majesty, the government and the Protestant religion: with a list of such noblemen, gentlemen and others as were the conspirators, and the head-officers both civil and military that were to effect it / humbly presented to His Most Excellent Majesty by Titus Oates.«

While Oates’ sober list of planned atrocities and corrupt characters reads like the description of a neutral observer, Hartmann’s story »Reiner Wein« is the psychological profile of a conspiracy theorist, a look into the mind of a person without a firm grip on reality, driven by fear and emotions. In his story, Hartmann does not refer explicitly to the coronavirus pandemic, but takes up arguments and claims that are common to many conspiracies. Nonetheless, a few of the objects from the photogram list also turn up in »Reiner Wein.«

A coincidence perhaps, showing how arbitrary and general most of the proposed coronavirus protection measures are?

Two photograms are laminated on each piece of cardboard and placed inside an envelope made of transparent paper, along with a title, a citation about their effect and application, and the source of the citation. The envelopes are printed continuously with excerpts from the short story by H.M. Hartmann and Oates’ Popish Plot. The German text »Reiner Wein« is divided into short sections and printed on a light-yellow background, in keeping with my mental image of a conspiracy theorist’s apartment walls pasted over with notepad paper and Post-Its. All twelve envelopes are stored in a hinged slipcase, a construction consisting of two interlocking slip-cases that open to a 90-degree angle so the sheets can be removed. This somewhat labyrinthine form not only corresponds to the folding of the individual layers, but also mirrors the thoughts of a conspiracy theorist, erratic and resistant to logical arguments.